In a series of 2025 publications, MHCI faculty member Kevin Volpp, MD, PhD demonstrates that gamification can significantly improve physical activity outcomes in health intervention programs. As part of the American Heart Association’s BE ACTIVE trial, Dr. Volpp and his colleagues tested behaviorally informed strategies aimed at encouraging people to walk more. Gamification emerged as the most cost-effective, producing sustained increases in physical activity and the greatest projected health improvements per dollar spent.

Gamification is the integration of game design elements like leaderboards, points, and badges into non-game contexts, such as education, civic engagement, and health. For example, the Duolingo language learning app uses leaderboards to motivate users to practice. The Starbucks app uses points and rewards to incentivize frequent purchases.

As part of the BE ACTIVE trial, Dr. Volpp and his colleagues tested gamification, enhanced by behavioral economics, to help participants achieve their step goals. Game components included:

-

A points system

Each week, participants were awarded 70 points. At the end of every day, participants who met their step goal kept their points, and those who did not lost 10 points. Deducting points rather than adding them leverages the principle of loss aversion, the phenomenon where people consider losses to be more significant than equivalent gains. -

The ability to level up

At the end of each week, the highest scorers would move up a level in the game, while the lowest would move down. At the end of the intervention period, the participants at the highest level received a trophy. This strategy attempts to improve motivation by including both immediate and long-term feedback and rewards. -

Social support and pressure

Every participant was asked to name a support partner. The partner would receive weekly performance updates about the participant and could nudge them to stay on track. This adds an element of peer pressure which, in turn, might motivate participants to stick to their goals.

Dr. Volpp’s team tested gamification against 3 other interventions:

-

Text message reminders, which they framed as the control group.

-

Financial incentives, in which participants were allocated a monetary reward that was docked if they did not achieve their goals.

-

A combination of gamification and financial incentives.

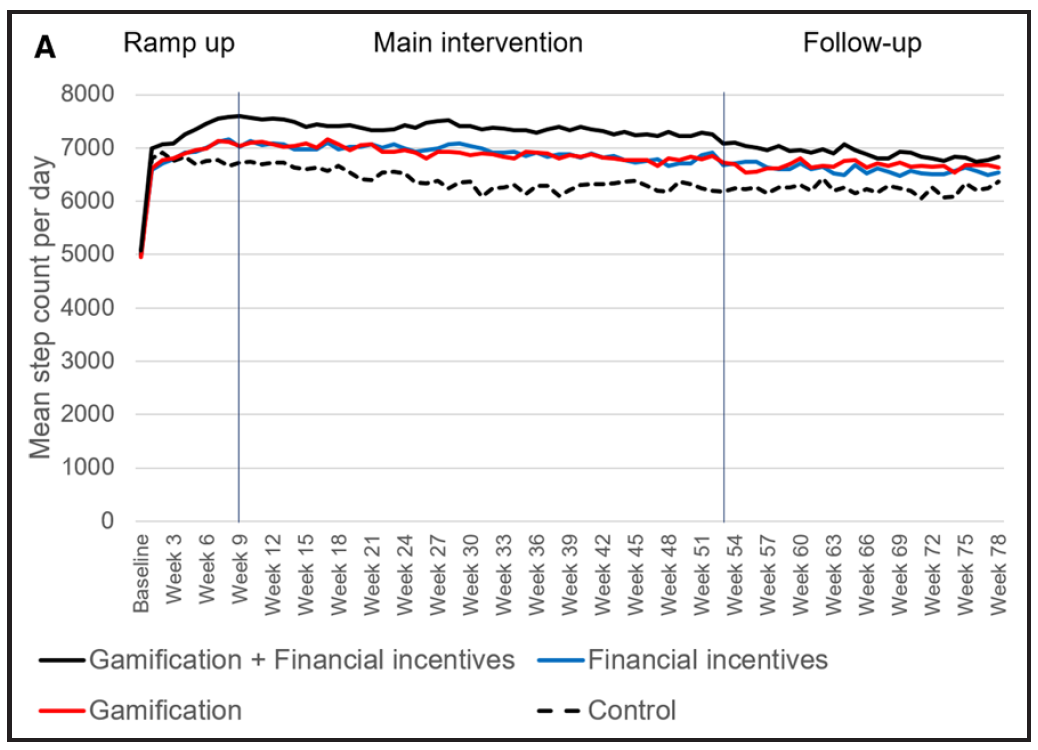

They found that participants in the gamification group performed similarly to those in a group that received financial incentives, and consistently better than the text message group. They also found that participants in both the gamification and financial incentives groups maintained their increased activity even after the intervention ended.

Figure 1. Average daily steps by intervention group, per week.

The group that received both gamification and financial incentives together outperformed all other groups in the trial. However, gamification offered the best value by a considerable margin, costing significantly less than the other interventions tested per life-year gained, even when calculated by conservative estimates.

Table 1. Cost effectiveness of each intervention compared to no intervention

Measuring cost of the program per life-year gained in optimistic, intermediate, and pessimistic post-intervention scenarios.

|

|

Gamification |

Financial Incentives |

Gamification + Financial |

|

Optimistic |

$5,119 |

$8,289 |

$7,629 |

|

Intermediate |

$11,471 |

$18,575 |

$17,110 |

|

Pessimistic |

$44, 547 |

$72,142 |

$66,550 |

Moreover, feedback from participants suggested ways that gamification could be enhanced. For example, some participants noted that their support partners were disengaged, and that they would have valued help choosing a more supportive coach. Others suggested that it might help if participants understood the rules of the game better at the start of the program.

Analysis of the feedback collected also suggested that a future program might benefit from a more targeted approach. Participants who are highly self-motivated may not have benefitted from any of the interventions as much as those whose motivation relies on external validation. And participants who are more intrinsically competitive may have benefitted more from a game that focused on beating their previous day or week’s score, rather than one with a strong social component.

This research points to an opportunity for health systems and employers: gamification, when grounded in behavioral economics, may drive meaningful and lasting improvements in physical activity at a lower cost than other types of incentives. For those designing or refining health improvement programs, gamification may present a scalable, evidence-based strategy with the potential for real-world impact.

Learn more from Dr. Volpp about how incentives and social pressure can be strategically deployed to improve health outcomes in his course, Behavioral Economics and Decision Making. Or learn, with a group of colleagues, to apply the basics of behavioral economics to workplace challenges through MEHP Online’s 4-hour, 4-week Behavioral Economics Workshop.