I vividly recall on November 8, 2022, fielding a question from a patient admitted to the hospital that I, and many other health care professionals, have heard on or around Election Day: can I go vote?

My initial reaction was to advise that it may be possible but, realistically, it could be complicated to coordinate with the limited time that votes are accepted and the complexity of casting emergency medical ballots. And it would be all the more challenging due to the short staffing that many facilities were experiencing.

While before enrolling in the Master of Health Care Innovation program, I may have accepted those responses as standard practice, I found myself newly inspired to look at the question through a different frame: how can we help patients vote?

The current answer to that second question—based on scholarly literature, health policy, and reform recommendations—is that it really depends. It depends on where the patient lives, the type of care facility they are admitted to, and the policy of the care facility itself. And that variability has moral and ethical implications, as well as a practical impact on patients’ ability to do their civic duty.

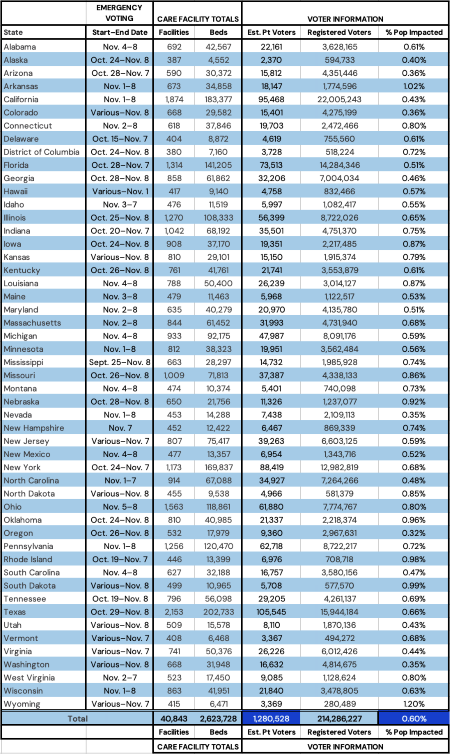

In general, each state in the United States has its own regulations for emergency voting. For example, patients who live in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania may start emergency voting about one week before Election Day, while those who live in New Hampshire can only cast their emergency ballot the day prior to the election, during limited hours. This may be further complicated by local or state requirements to file certain petitions in person, or to complete emergency ballots in ways that many local hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and other health care institutions are currently not structured to accommodate.

Table 1: State-specific review of emergency voting start and finish dates, total number of care facilities and beds, and a granular estimated number of potentially disenfranchised individuals per state, as of November 2022.1, 2, 5, 6

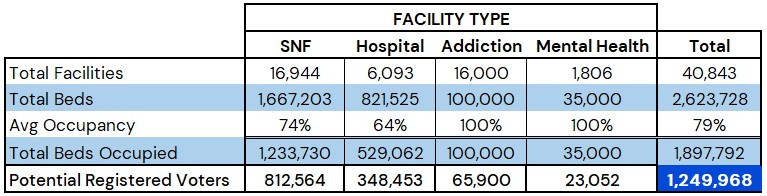

The specific type of health care facility where patients are housed also has an impact, surfacing critical ethical questions pertinent to voter disenfranchisement. A common theme I found in existing scholarly literature is that patients’ ability to participate in elections is not a high priority in many types of care facilities. This includes traditional inpatient hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, addiction or substance treatment centers, and inpatient psychiatric care centers.

We may think of inclusion for patients who are undergoing treatment for addiction or substance abuse, or those who are under psychiatric care, as controversial. However, the inclusion of this population is ethically important: outside of care facilities, individuals do not have to pass a test, prove their sobriety, or provide mental status clearance to vote in an election. Knowing this, it would be unreasonable to exclude this population from voting, provided that they are able to make independent decisions.

Based on U.S. Census and voter registration data, around 66% of the population in the United States is registered to vote, which equates to just under 215 million voters. If we assume patients admitted to care facilities are representative of the general population—meaning that they are as likely as any other American to be registered to vote—we can estimate that there are 1.25 to 1.28 million in-patient voters on any given day.

Some patients are admitted and discharged within the window of possible medical emergency voting; they are not physically or psychosocially able to go vote. This population increases the number of patients disenfranchised on any given day to1.3 to 1.35 million, 0.60 to 0.63% of those registered to vote.

On the surface, it seems inconsequential if fewer than 1% of the population registered to vote is not able to cast their ballots. But according to a 2018 NPR report, almost 20 elections between 1991 and 2018 were decided by fewer than 10,000 votes, including ties and contests that were won or lost by single digits.7 The outcomes of both the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections hinged on fewer votes than the number excluded because of hospitalization. Even a small percentage can have a significant impact.

Table 2: Summary of various key data points on the average day in the United States. 1, 2, 5, 6

The scale of this disenfranchisement gives rise to a number of important policy and research questions, including:

- What are the full ethical and moral implications of de facto denying admitted patients the right to vote?

- Are there populations—such as those who are unconscious or lack capacity—who should be denied their right?

- Might there be unforeseen legal, political, or operational repercussions of making it easier for admitted patients to vote?

- What steps can we take to facilitate voting in a way that is convenient for patients, sustainable for care facilities, and within the bounds of what is allowed by each state?

As stakeholders from health policy, health care business, and clinical policy continue to work together to improve equitable approaches to care for patients, one factor we should certainly integrate as a standard of care across every health facility within the United States is ensuring that patients have uniform access to their Constitutional right to vote.

Blake Tobias Jr., MHCI, MS HA-ODL, a first-generation college graduate, is a research biologist turned administrator with a strong reputation for pivotal and innovative leadership. He is currently a Senior Regional Practice Manager overseeing a dozen clinic locations across Pennsylvania and New Jersey for the Penn Medicine Transplant Institute. Blake completed his Master of Health Care Innovation in 2023 and continues to introduce new research and innovative business strategies into his community to provide those in need with access to high-quality care.

(1)"Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2022," American Hospital Association, Jan. 2022, www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals.

(2)"Hospital Statistics by State." American Hospital Directory, per Medicare Cost Report, 26 Sep. 2022, www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html.

(3)"How to Vote." Patient voting, Vote from your hospital bed, www.patientvoting.com/howtovote.

(4)McBain, R. K., Cantor, J. H., & Eberhart, N. K. "Estimating psychiatric bed shortages in the US," JAMA Psychiatry, 79(4), 2022. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.4462.

(5)"SNF Statistics by State." SNF Data, per Medicare Cost Report, 18 Apr. 2022, www.snfdata.com/state_statistics.html.

(6)"United States Population," World Population Review, Mar. 2023, worldpopulationreview.com/countries/united-states-population.

(7)"Why Every Vote Matters," National Public Radio, Nov. 2018, www.npr.org/2018/11/03/663709392/why-every-vote-matters-the-elections-decided-by-a-single-vote-or-a-little-more.